A Meander Through a Brain on November 10th

Don't try to find order in this one

My husband and I have adopted a little gardening quip for our own experiences of moving and rooting and bearing fruit in life. The quip refers to perennial plants: “The first year they sleep, the second year they creep, and the third they leap.” This has become our sort of personal timeline of life after a move (of which we’ve had many).

Last night, around the dinner table with a new friend, we tallied up our time here in The Little River Cottage and in September, as it turns out, we crossed the threshold into year three. But I feel about as far from “leaping” as I’ve ever been before. Perhaps it was the pandemic, a year plus of closures and stalls and trying to remember what faces looked like, and we can adjust our timeline a bit, add a year or two onto the adage.

But really I just think the older a perennial is, the harder it is to move.

This could go a lot of ways, but mostly I’m thinking about my recent move away from sayable.net to lorewilbert.com. The change is only for the good (from my perspective), but it feels a bit hard for me to uproot from that space and come here. I don’t know why, but it’s good for me to say aloud. I feel as though I’m still exploring the corners of this new home and testing out her floorboards and feeling a bit afraid to take up space.

Speaking of taking up space, the older I grow the less space I want to take up. I see all the memes on the social media about being brave and stepping into your place and taking up all the space you need and blahdy-blah, but mostly it just falls on me in sort of a hollow way. I don’t know what exactly that means in real life? If it is just permission to show up in social media as another competing voice or in the cacophony of cheerleaders all saying a different version of the same thing (I’m guilty here, don’t hear me wrong), then I’m not sure I’m interested in that kind of taking up space. And yet, I very much believe that the way to human flourishing is to, in the words of Andy Crouch, be “magnificently oneself.” Being oneself in its very nature means to take up exactly the space of one’s own self.

I tapped quickly through my Instagram stories this morning and every single one of them was telling me either the same exact thing using different words or such wildly different things that my brain just simply couldn’t handle it all, and I closed the app.

I don’t have plans to quit Instagram like the lovely Tsh Oxenrider, though I’m perilously close to quitting Twitter and Facebook almost all the time (for now I’m just passively quitting both by rarely logging in). I like beauty and art and makers and creativity and, for now, Instagram is the place most likely for me to find it. I also like sharing what I hope is beauty and peace in that space, though I could very well be a part of the cacophony as well. How can I know?

This short little documentary on William Morris, the Arts and Craft Movement, and Philip Webb came across my feeds recently and I was freshly inspired to evaluate the beauty and usefulness of my working tools again (this is an exercise I undertake far too often I think). Morris & Co. believed that all useful things should also be beautiful things. One of Morris’s more famous quotes is, “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful,” and this has always been a rubric for the homes I’ve tried to make. I’m interested not only in the practicality of a thing, but also in its ability to be aesthetically pleasing—at least to the inhabitants of the home.

It’s also been the rubric for the tools I use in work, which these days takes place primarily online, which can often feel to me like a desecrated place that’s only becoming more and more desecrated. But I’m also reminded of Wendell Berry’s words in How To Be A Poet, “There are no unsacred places; there are only sacred places and desecrated places,” and know there is an alternative (to make sacred) but one which takes an intentionality that feels too hard to stem most days.

The truth is, dear readers, I’m tired.

I’m a tired perennial who’s been planted and uprooted too many times in my life and my roots have been chopped and my tendrils dried out and the holes too shallow and the weather too uninhabitable. I am not creeping or leaping and most nights I’m even having trouble just sleeping. I’m tired.

I’m tired of having to be intentional about everything. I’m tired of evaluating everything. I’m tired of reevaluating everything. I’m tired of judging the old me and the ones that hurt me. I understand why people get set in their ways and I don’t think it’s because they’re all stubborn, I think it’s just because at some point, we just. get. tired. Our attention isn’t held by the same things it used to be held by, and our sense of calling becomes more narrow and focused, and we realize the things that really matter for us are much more limited, and are somehow both more complex and less complex at the same time.1

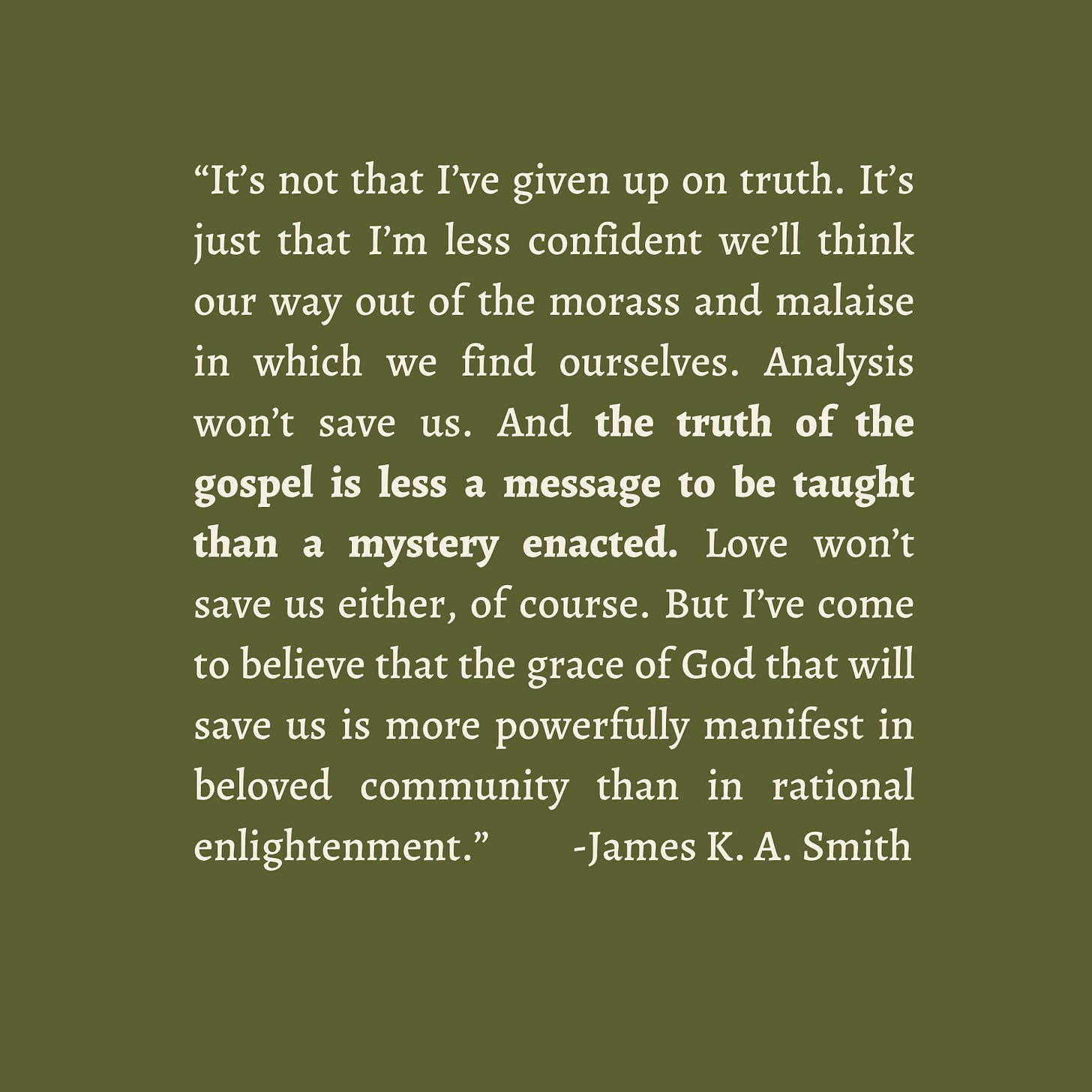

I am aware of the dichotomies and lack of binaries in life in ways today that I didn’t have space for a decade ago. And yet, I’m much less precise in my own beliefs and practices than I was ten years ago when I was constantly afraid I would waste my life or miss my calling or someone would wrench it from me for themselves. Those two truths make it easier for me to disengage from the virtual world and be more engaged in my actual world. More than ever, I agree with James K.A. Smith that, “it’s not that I’ve given up on truth. It’s just that I’m less confident we’ll think our way out of the morass and malaise in which we find ourselves. Analysis won’t save us. And the truth of the gospel is less a message to be taught than a mystery enacted. Love won’t save us either, of course. But I’ve come to believe that the grace of God that will save us is more powerfully manifest in beloved community than in rational enlightenment.”

In our Spiritual Formation program we talk a lot about stages of faith or belief or power or growth, and there have been times in my life when I’ve pushed against that sort of talk. I see now I was pushing back on it because I didn’t like being categorized in a sometimes unlikable stage. There are stages where we get our power from who we know or what we accomplish. Or stages when our faith is more rooted in our communities or cultures. Stages where we get our cues for what to do by looking around us at either what everyone else is doing or what seems to be the most felt needs around us. But one thing all these stages have in common is that eventually, whatever stage we’re in, it simply stops working for us anymore. We see its limitations or we see our own selfish ambitions wrapped up in it or we see how much more we desire wisdom over knowledge. And when that transition happens, if it happens fully, we begin to become more tender to those in the stages before us, where we once were and thought we were so right about.

Smith says that analysis won’t save us, and so I don’t want to analyze the whys and goods and means of all those stages. I find the naming of them helpful now because I feel adrift in some ways now and that might have scared me at one point (and maybe should scare me more than it does now), but mostly I just know where I am and am not afraid of what being here means.

If the gospel is a mystery to be enacted, then what does that mean exactly? What does it mean for the transient human who has no roots? What does it mean about a website migration? Or usefulness and beauty? Or Instagram and online presence? Or dichotomies and binaries? Or stages of faith or love or any of it?

But the very nature of asking that question defeats what Smith was trying to convey. Encapsulating the mystery solves it and then it becomes a thing to be analyzed.

More and more I just want to sit with people in their pain and grief, sit through it with them. Ask them questions if it seems helpful, but mostly just be with them. More and more I find the most useful thing I can do as a human is to be beautifully present with the people in my life, with the story they are living right now, and that’s pretty much it.

It makes the work I do in these spaces tough, though, because I’m much less inclined to bring any wit or wisdom I might have to these places anymore and much more inclined to stop analyzing the world and instead just be in it.

It occurs to me that the work of a perennial is not to evaluate the soil or complain about the weather or fetch its own water. The work of a perennial is to submit to its environment (Provided it’s in its proper environment—you can try your best but peonies will not flourish in the desert, nor will cacti in the northeast.), receive what it has to give, and trust the blooms will come. The work of a perennial is to be magnificently itself, to lean into the mystery of its intention and not worry itself asking why it isn’t a blooming annual instead.

Have you ordered my newest book? A Curious Faith: The Questions God Asks, We Ask, and Wish Someone Would Ask Us. Available now, wherever books are sold: Amazon | Baker Book House | Bookshop

Also available: Handle With Care: How Jesus Redeems the Power of Touch in Life and Ministry

Find me on Instagram | Twitter | Facebook | My Archives

Parker Palmer’s book Let Your Life Speak is hugely instrumental in helping me with this.

My goodness. If this is you just being beautifully present online, I'm here for it. Your words bring life and hope to me. Thank you.

Lore, as you describe the perennial plant and how you just want to be, this thought came to mind. Your book, and often your writings online, have such good questions. I wonder if you are entering a season of listening. Listening to perhaps answers to some of your questions. Listening to God. And maybe giving the gift of listening to others in your realm who have a desperate need to being truly heard. To offer the hospitality of your heart by listening and just being with. 🤔♥️