Knock, Knock, Knocking on Heaven's Door

What do we do when we've lost faith in the Bible but still want God?

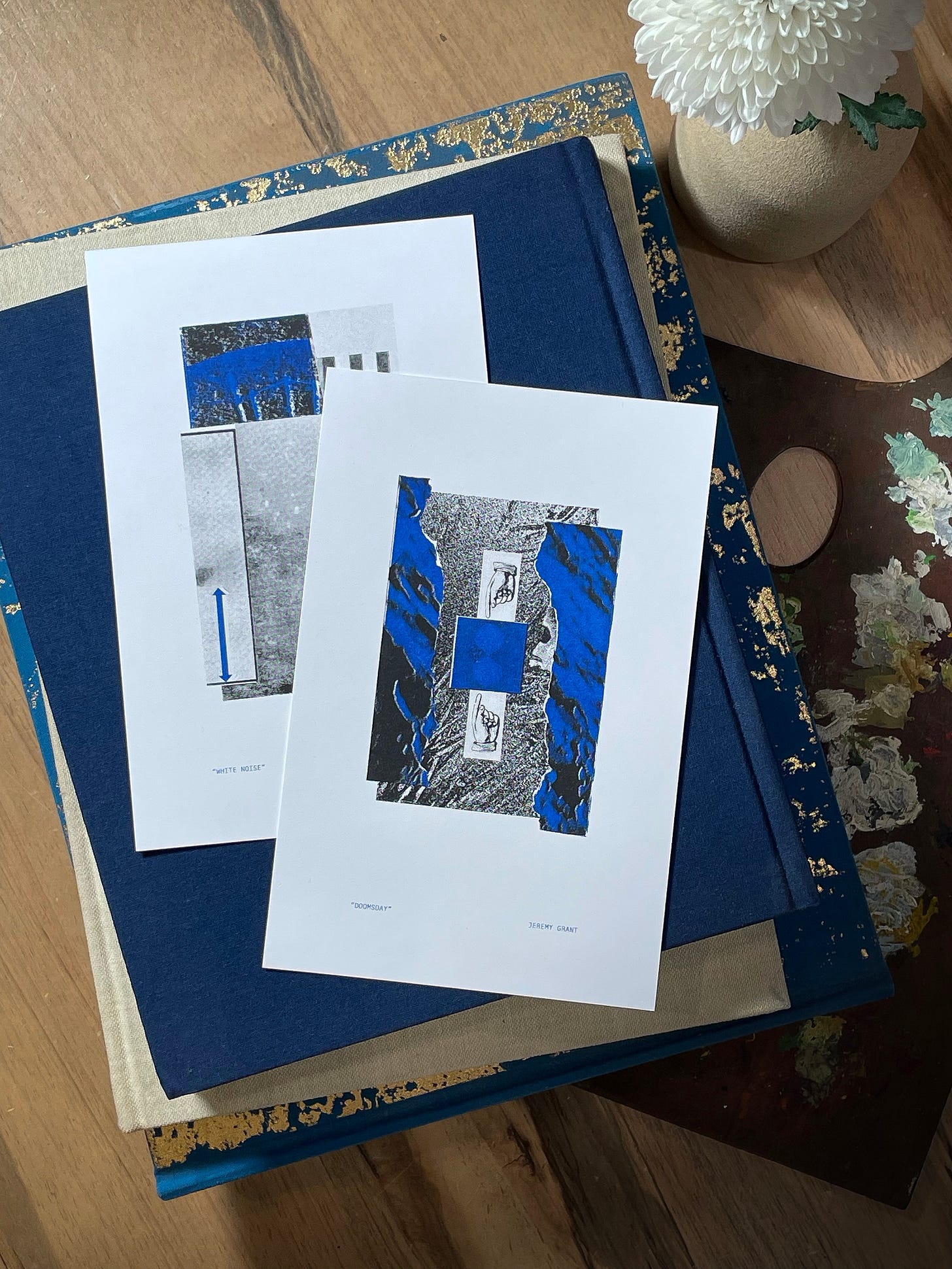

There is a giveaway at the bottom of this post. Don’t miss the chance to win four of the art prints from the book. They’re gorgeous!

Several years ago someone asked me, “What do I do when I can’t read the Bible anymore?” I imagine it was a question rooted in pain or grief or loss, and I lamented for the asker, having been there before and knowing I would be there again.

It was actually during a class in my graduate program where the lightbulb went on for me and I could stop shaming myself (and, quietly, others) for difficulties around reading the Bible. I wrote more about that here, but the short of it is I realized how much my whole Christian faith had been built around the things of God instead of God. I had oriented my faith around the church, the Bible, the people of God, but kept losing sight of God at the center, and whenever that happened, I would dissolve into doubt, knocking my fist at the sky, demanding God to show up. But when I began to shift this orientation, keeping Jesus at the center (I share a graphic of how this looks for me in the linked post above), I realized my relationship with the Bible, and all the things of God, were forever altered. I stopped feeling far from God because God was never far from me, it was the things we humans made in our attempts to see God or be like God that were far from God. And if we could just admit that, and admit that in our imperfect attempts, we were still trying, well, I thought that could change a lot.

And for me it did.

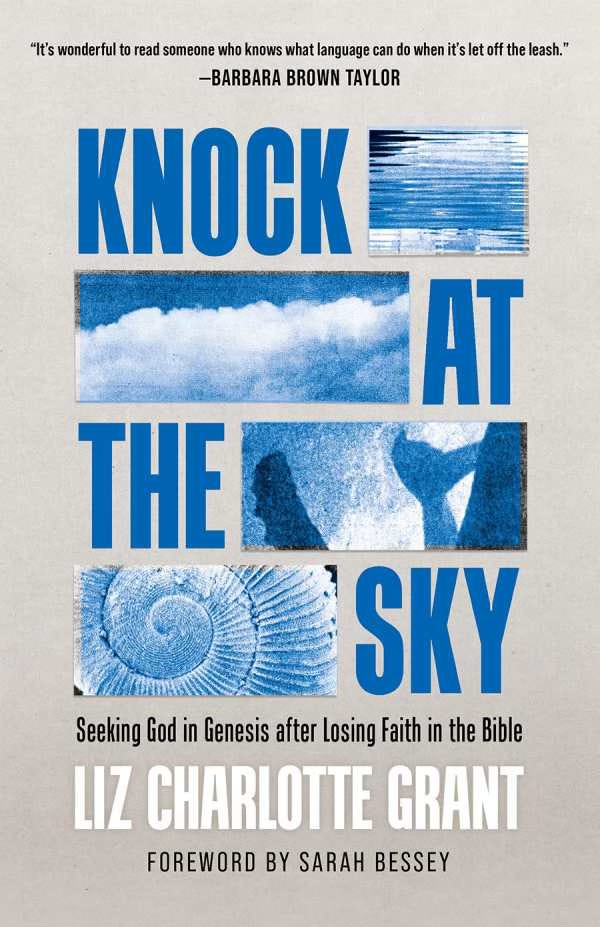

Liz Charlotte Grant has knocked her own fist at the sky a time or two and now she has released her first book, aptly titled Knock At the Sky: Seeking God in Genesis after Losing Faith in the Bible. The book itself is gorgeously written and is just the kind of combination of science/art/history/spirituality that wets my whistle. I love a good integration, and Liz nails it in this book. I hope some of you who may also find yourself struggling with reading the Bible will pick this book up and experience wonder afresh. The world is a wonderful place and God made every inch of it to be discovered and loved. Enjoy!

Lore: You open the book saying, "I am not ready to cede the Bible to the literalists. While some of my formerly evangelical peers prefer to ditch this often-troubling book altogether, I refuse to. These stories are mine too." Talk to us about what it means for you to not cede the Bible to the literalists, and perhaps what it means to not cede the total dismissal of the Bible to the other kinds of literalists—those who have no room for it at all.

Liz: When I first pitched this book with my agent back in 2022, we were told by one editor that progressive Christians don't read books about the Bible, and so this editor was not sure what kind of market existed for a book like mine. I found this answer striking and indicative of a trend I was seeing amongst those who were vocally "deconstructing"--to many of the most liberal, the Bible was deeply problematic, and not only because it had often been used against them as a tool of spiritual gaslighting. The stories and characters themselves evoked an ancient world no one wanted to remember or be associated with. The idea was, well, as progressives, we've moved beyond this medieval book with its power hungry, bloodthirsty God. I found that attitude almost as troubling as that of my conservative fundamentalist ancestors who read the Bible flatly, without context or commentary, but as if the biblical authors had been writing in midwest America in the twentieth century to midwestern Americans in the twentieth century.

The Bible should be read both plainly and with great context and nuance. And I would argue that we cannot escape the influence of the Bible in Western culture, even if we deconvert from Christianity individually. The deeper. biblical themes and characters have profoundly shaped the European and American imagination, as we continue to see today (and not just in the arts either, but in our politics, too!).

And I argue in the book that to deprive ourselves of these biblical narratives as Christians is a death by starvation. We are depriving ourselves of the spiritual wisdom, narratives, and realities of our ancestors' encounters with God. God is certainly beyond the Bible. And yet the Bible has sustained spiritual travelers for hundreds of generations, beginning with the Hebrews and into our own time. So I believe it is pure chronological snobbery to assume that we have nothing to learn from this ancient masterwork or that God no longer speaks through these words.

That said, I cannot claim that everyone must engage the Bible in the same manner or frequency. Those who have been spiritually abused and/or those who have had the Bible used as a weapon to undermine their agency should likely not engage the Bible for a time. Some passages may remain painful to read, and I suggest that Jesus allows for this sort of individual creativity in how we approach the Bible. We can center and marginalize certain passages with freedom, both as communities and individuals, based on the Holy Spirit's leading, our own individual discernment, and based on communal practice. That does not mean the central themes and messages change. Nor does that mean there is no objective truth that undergirds the universe. But I believe that God is gentle, especially with those who have experienced harm. And I believe that acting as spiritual adults, rather than children, allows us to practice discernment and wisdom as we approach God's precious book so that we can receive it --and Godself-- as a gift, rather than a burden.

Lore: You write, "I have written this book as an experiment in eisegesis, as in, reading life into the biblical text." I loved this sentence for so many reasons, but especially your use of the word experiment. Often when it comes to book publishing, authors feel boxed into writing a sort of 'final word' on something, more defense of thesis than trial and error. But my favorite kinds of books are experiments, their authors are explorers, and they're willing to tell the truth about what they find on their journey, even if the truth is not convenient (and it rarely is) or not even the final truth. Did writing this book really end up feeling like an experiment for you? How so? What questions were you still left with at the end?

Liz: Absolutely, this book is a wide open experiment for me, from start to finish. I am not a theologian, not a biblical commentator, and I have not attended seminary. Rather, I'm a creative writer, and I wear that badge proudly, though I did not always feel confident during this project.

This project forced me to face my own imposter syndrome about being unqualified to write about the Bible. I had considered attending a local seminary several times, even applying, but I could never justify the expense. I wondered, who was I to explicate the first stories of the Bible? My book went through a couple rounds of theological editing with the Eerdmans editorial team, and I can tell you I was trembling at home waiting for my theological editor to return the manuscript to me. I was sure I'd done it wrong, that I'd gotten the Bible wrong. Turns out, I was more right than wrong in my close reading, but still, when you're writing about an ancient book and you're unqualified to do it, you need that expert perspective, and I'm deeply grateful to have had that. Eerdmans did not do a theological edit to make my thoughts align with their theological and interpretative preferences, by the way, but rather a scholar of the Ancient Near Eastern culture and manuscripts read through my book to offer critical analysis and to fact check my conclusions--and that's different than how other Christian publishers would have edited this book.

I also had fabulous advice from a mentor early on. I asked him, should I be writing this book about Genesis without a seminary degree? Should I go to seminary first before I write this book? And he strongly discouraged seminary. He told me that my perspective--the perspective of a creative writer--was exactly the perspective I needed to bring to Genesis, and in fact, the academy could diminish some of the uniqueness of that perspective. I found that convincing enough to keep writing.

But there was no straight line to finishing this book. It took many tries to find the structure, to discover which disparate stories of science and the fine arts belonged next to which exegesis of Genesis, and I was editing up to the very last second.

The tone was also difficult. My writing voice tends to be casual and familiar, and my editor encouraged me to streamline, to lean more literary. But I was convinced that my particular audience would appreciate the tone of the guide, journeying alongside, that I needed to sign post more than I would for a literary audience because my readership would be less familiar with the braided essay form (the literary form I ultimately chose for my book). My agent had encouraged me to add more personal stories in the first person. At the time, I felt allergic to memoir because I'd just failed to sell a memoir, and I felt sick of my own voice. But he was right! That helped me define the perspective as a fellow traveler. But it was a trick to find the right balance. I have thirteen or so drafts saved on my computer of the manuscript in different forms, including a document called "extras" with the outtakes that did not make it into the final draft. I'm still not sure if the form is exactly right, but at some point, your editorial team locks you out of the document and you have to accept that it's good enough to publish. Then you release.

Lore: In your chapter on God's image, you write, "Our existential hunger will not rest. We need to know who we once were and who we are becoming." Who have you become as you wrote this book and how is it different than who you once were?

Liz: I think this book is a reflection of my own changing faith, but I'm not sure I'm different after its writing. "I used to be a good evangelical," I write in the introduction, and I have the evangelical credentials to prove it.

My faith as a young adult was intimate, charismatic, and deeply entrenched in evangelical church culture, including in patriarchy. I talked to Jesus personally, and Jesus talked back. But I had a deep sense of my wrongness. Why did I want to lead, teach, write if God had made me a woman who wasn't supposed to have these giftings? I had a troubled relationship with my family, which I felt was probably my fault. I also hated my body, a product of being raised by a mother who despised her body, too, and always had the sense that my body was wrong. This was partly internalized misogyny, but I was never the ideal barbie body type, and as I became a fat woman (I weigh over 200 pounds), this sense of wrongness increased.

The move toward a more inclusive, progressive faith, in this context, was a way of seeking freedom and healing. I needed to come to terms with the gifts --truly the generous gifts--that God had given me, the shape of my beloved body that God had made and continued to sustain on my behalf, and my own power that God had offered to me when God created human beings with freewill.

Of course, my shifting mind also initiated a change in how I interacted with God. I have heard that a mid-faith slump is normal, and I have certainly experienced that in my mid-life. For me, that does not mean that my trust or belief in God has dimmed (it has grown!), but that God has seemed more distant. I do not experience the same clear speech from God as I used to. I do not read the Bible like I used to for "daily instruction." But I still feel certain that God will keep illuminating each next step of my life, that God has given me freedom as a spiritual adult to keep walking (even if I'm in the dark!), and I have confidence that I cannot step outside of God's abiding love and care. Just as mid-life marriage is more settled, grounded, and less dramatic than early infatuations, so too my relationship with Christ. I appreciate that stability. And I'm grateful that “God plays in ten thousand places,” whether I'm aware of it or not.

Lore: You write, "Consider how an infant's retreat from the mother does not begin at birth but conception, when the fetal cells split from hers in utero. Pregnancy is an act of creation by separation. For mother and child to survive past pregnancy, an infant must be expelled, and the umbilical cord must be severed. The cord supplies oxygen during fetal development, but as the fetus matures, the cord impedes further growth. The mother cannot breathe for her newborn forever. The newborn must test her own lungs. God understands that untethered love is the only love worth having." This idea of untethered love, and your connection making with free-will, may challenge many of us who once found comfort or security in something like predestination or the eternal security of God's love for the world. What would you say to someone wrestling with free-will and the scarier sides of what that means?

Liz: I have so much compassion for those who see freewill as terrifying! As my faith has shifted, I have had to wrestle with this question for myself--what does my life mean if God is not directing every second for some unseen spiritual purpose? Am I on my own if I'm making my own choices and God is observer, not main actor? What level of involvement does God actually have in my day-to-day life?

When I consider God's commitment to our freewill in my book, I actually do not mean to say that God is distant, that God does not care, or that God does not act. The Scriptures show us a God who is deeply involved, interested, and near to God's people. But God does not smother. God is not an authoritarian. We see this even in Revelation. At the end of time, when Jesus arrives to judge, Jesus stands at the door and knocks. (Revelation 3:20) Jesus extends an invitation. Jesus does not bust in with guns blazing like a cowboy. Rather, Jesus knocks. I marvel at the humility and gentle invitation of our savior here, and I find it instructive.

The fact that an individual can choose God matters to God. I often think about C.S. Lewis's The Great Divorce, in which hell is a person's purposeful retreat into greater and greater aloneness. Hell, in Lewis's fictional telling, is a choice to place distance between a person and others, including God, and that distance is its own torment.

Then again, I do not claim to have figured out the complex dance between freewill and predestination, far from it! Later in the chapter you quoted from, I discuss the importance of deconversion in healthy religious spaces. In authoritarian or abusive religious communities, deconversion, deconstruction, even questions are disallowed. I argue that this kind of faith is like Stockholm syndrome, and it does not grow healthy belief in an individual or a community. So, the point I'm making about God's untethered love is actually my way of correcting my own tendency toward a theology of predestination. I cannot solve the paradox of my agency and God's agency, and I do not know if the Scriptures solve it either. What is needed, more than settling on one theology over the other, is the humility to say, I don't really get it. I have no clue which wins out. But I trust God.

Lore: Nearing the end of your book, you write, "I admit I fear being wrong about God. What if I have received God with confusion instead of clarity? My native Evangelicalism values certainty. Like the scientists of the Enlightenment, we prefer to quantify, measure, sift, and bottle. We value argumentation and decisiveness; we dismiss doubt and paradox. If we could catch God in a net, pin God to a board to collect dust, and then study God from every angle, I suspect we would do it...Yet I am beginning to suspect that the hike toward God resists a plan. Does any one of us contain the map of spirituality? Wandering may be inevitable." Recalling your words from the beginning of the book about experimentation, do you think we are forever bound to a life of trying and seeing? Do you think God made us to wrestle with our existence and God's existence forever, to never truly settle into the wholeness of the studied God? Is there a time when our wrestling needs to cease or would you say that is where fundamentalism begins to creep in?

Liz: At the end of my grandmother's life, when she was hallucinating and reliving her past lives after a stroke at age 94, I got to witness her finally settling into God's peace. After a lifetime of facing anxiety, grief, abuse, questions, and unanswered prayers, I could see and feel her release into God. Frankly, I do not believe any of us will settle the question of God until the very end, if we even do before we cease to be. We just do not know what happens during and after death, and I believe the question remains with us throughout our lives. In fact, I believe faith itself is this ongoing wrestling with God. That has become the very definition of faith to me, as it was for the Jewish people who adopted the fate of the patriarch Jacob as their collective fate. Wrestling is the ongoing relationship we have with God, and that is The Work that forms, refines, and clarifies both God and ourselves. Even so, I believe we do have flashes of inspiration like lightning in which God allows us a glimpse of God's self. The dim mirror clears, if only for a second (as Paul talks about in 1 Corinthians 13). And that's the reason we continue to struggle, in hopes of seeing in the dark.

Lore: You write, "In the end, what has sustained me in my reading is humility. Bible study, for me, means constant repentance. I see that I must constantly be willing to turn around, change my mind, admit that I've taken the wrong meaning from the text, and accept correction." Apart from your "for me," there seems to be the implicit sense here that the evangelicals from whom you have come apart, those who may pride themselves on Bible study or Biblical literacy, are those who don't change their minds, but ascribe to a kind of "The Bible says it, I believe it," kind of spirituality. I know people who do say things like that and call their faith "simple" or "not complicated." For them it's less about hubris and more about not questioning the plain words of the Bible. But for you, the whole of this book is about wrestling with the reality that there is not one single plain word in the Bible. What would you say to someone who would say that their plain reading of scripture is also rooted in humility?

Liz: Again, I very much understand this way of thinking. First, I do mean to make clear that I wrote this statement with myself in mind. I cannot know the motives of other individuals as they approach the Bible or God, and I would suggest that there is a difference between the group as a whole ("evangelicals," and especially "white American evangelicals") and its institutions versus those individuals who consider themselves evangelicals. So, while I certainly had evangelicals in mind as I wrote that statement, I meant the group from whom I came, not any particular individual.

Early in the book I say, "Certitude is a trait of my people," and I have no qualms about saying that, as a group, evangelicals are not humble. We are demanding and our theology has authoritarian undertones to it that places ourselves at the top of the heap (just look at the cultural example of evangelicals set out by the Heritage Foundation and Project 2025, an organization with close ties to the authors of the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, a document that was drafted in 1978). As a culture, white American evangelicals believe ourselves to be superior, chosen, predestined, and the center of the story. We are the new Israel, right? This is not only an evangelical problem, but also an American problem. And this is not only an American evangelical problem, this is a white American evangelical problem, with our history of racism and hierarchies. Put these all together and you have quite a tangle of hubris and ignorance.

I do believe that the Bible is still, at some level, despite our close study, unknowable.

Second, I do believe that the Bible is still, at some level, despite our close study, unknowable. I believe this is true of all true works of art. The nuances of a masterwork continue to reveal themselves over time because art does not expire. As long as people continue to engage it, art will keep speaking into new times, people, and places. As we change, therefore, so does how we read the book known as the Bible, and I cannot presume to understand its full depths at one particular moment any more than I can presume to understand my husband fully at any particular moment. Art is an ongoing relationship.

Last, to answer your actual question (ha): what would I say to someone who would say that their plain reading of scripture is also rooted in humility? I would ask them how their faith has changed over time. How have they changed their mind? How has God's shape changed in your vision? What nuances, shadows, or new words have allowed you greater insight, or have put God into greater relief? How has God become more mysterious?

By this, I mean to poke at a person's understanding of humility. Isn't humility, fundamentally, about changing your mind, about being open to the changing world as it appears before you, about the realization that you might have gotten it wrong? The basis of a belief in inerrancy--which often undergirds the faith of those who insist upon a "plain reading" of the Bible--is that the whole knowledge of God can be known. (This is called presuppositional apologetics, and I suggest that anyone who resists this conclusion look up its controversial twentieth-century founder, Cornelius Van Til.) And I simply disagree.

Because the Bible is a book about God, I believe that it holds some of the same luminous mystery of God which, as I mentioned before, cannot be bottled. How could it? To contain God is to reduce God. And the God of the Bible is uncontainable, the one who created clouds but also becomes a fleshy, fragile body. I believe that, when we're being honest, our understanding of God, ourselves, and God's book cannot help but change.

...but then again, I could be wrong about that. ;-)

Lore: I love that. Thank you for doing this interview. I hope my friends pick up your book.

Purchase Knock At the Sky through this link and support our friends at Nooks Books:

Giveaway!

We’re giving away four of the gorgeous prints included in the book and to enter to win, just leave a comment below with one of your favorite lines from this interview. Just cut and paste from above, and boom, you’re entered to win. I’ll announce a winner next week and reply to your comment to let you know you’ve won.

“I have heard that a mid-faith slump is normal, and I have certainly experienced that in my mid-life. For me, that does not mean that my trust or belief in God has dimmed (it has grown!),”

Wow! What an interview! Three quotes really resonated (sorry, like Miss Bates, I couldn't limit to just one): "The Bible should be read both plainly and with great context and nuance."

"For mother and child to survive past pregnancy, an infant must be expelled, and the umbilical cord must be severed. The cord supplies oxygen during fetal development, but as the fetus matures, the cord impedes further growth. The mother cannot breathe for her newborn forever. The newborn must test her own lungs. God understands that untethered love is the only love worth having."

"Wrestling is the ongoing relationship we have with God, and that is The Work that forms, refines, and clarifies both God and ourselves."

Thank you!